Father's Day: Here's to you Ace Cleveland

Posted on: June 15,2013

(My father, Ace Cleveland, died 18 years ago, and, still not a day goes by when I don’t want to pick up the phone and call him. It might be to tell him something that just happened in the Braves game. It might be about something I just read. I might need help with the New York Times crossword puzzle. I might want to ask him about one of his

recipes. I might need some advice. Or I might just want to hear that gruff voice and dry sense of humor. Instead, sometime today, my brother Bobby and I will fix Ace’s Hattiesburg-famous Bloody Mary recipe and we will have a toast: to Ace.

recipes. I might need some advice. Or I might just want to hear that gruff voice and dry sense of humor. Instead, sometime today, my brother Bobby and I will fix Ace’s Hattiesburg-famous Bloody Mary recipe and we will have a toast: to Ace.What follows is a column I wrote about my father years after his death when he was inducted posthumously into the USM Alumni Hall of Fame.)

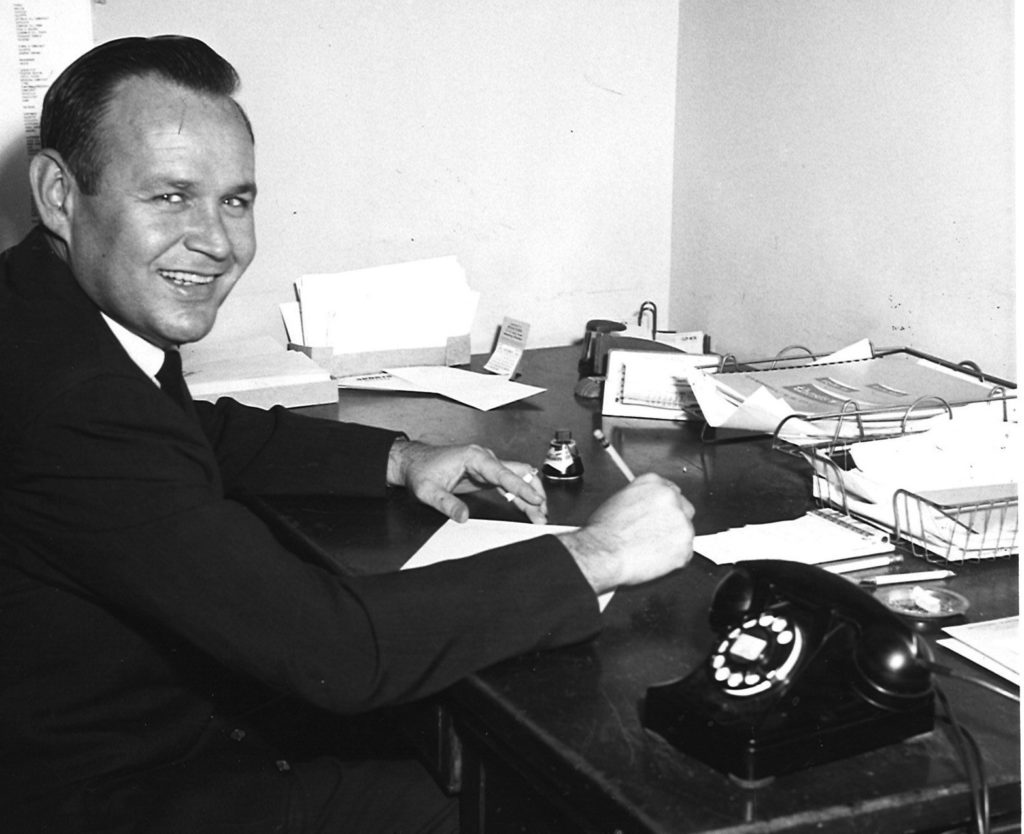

THIS would have been about 1956. Our dad, Mississippi Sports Hall of Famer Ace Cleveland, was the publicist at what was then Mississippi Southern.

Our mama didn’t work. She was too busy raising two little hellions and trying to ensure they weren’t forever warped by their environs.

We lived in the Old Rock, a dormitory that housed athletes. It is underneath the east side of what the stadium now known as The Rock — and, as the saying goes, if walls could talk. . .

My brother, Bobby, and I couldn’t have been happier. Our playmates were ballplayers, and they treated us like kid brothers. We learned words most toddlers don’t.

One of my earliest memories is of supper one night when Bobby reached over and grabbed the last chicken leg. He was 3. I was 4.

“Bobby, you S.O.B.,” I said, as if I knew what it meant, “if you eat my – – – – – – – chicken I’m going to kick the – – – – out of your scrawny – – -.”

Ace, the late Carrie Cleveland and Doc Harrington, who will be inducted into the Hall of Fame on August 2.

Mama cried. Daddy tried not to laugh. And I immediately developed a lifelong dread of the taste of Ivory soap. I also learned I probably ought not repeat everything I heard down the halls.

Southern was a small college football terror. In my memory of those days, the Southerners never lost. (They almost never did.)

One Sunday afternoon after a big Saturday victory, Daddy decided to celebrate with a steak cookout, a rare treat. I don’t know what the poverty line was back then, but we were straddling it.

When his prized meat became engulfed in flames, he hurried inside for water. We ran back outside with him, only to see two guys scurrying around the corner — with not only the steaks, but also the still-flaming grill.

The thieves had to be athletes, because they ran faster with the grill than Dad ran without it. They got away. We ate tomato soup.

This weekend, Bobby and I attend Daddy’s fourth Hall of Fame induction. The last two have been posthumous, so we can’t say for sure, but we think he might get the biggest kick out of this one.

The first three inductions – to the Mississippi Sports Writers, the Southern Miss Sports and the Mississippi Sports halls of fames – all involved sports.

This one – the Southern Miss Alumni Hall of Fame – does not. This one is for distinguished service to the university and for business and professional accomplishments.

Rule No. 1 is that you must have graduated, and Dad almost didn’t. He quit college to go to work in 1949. He knew what he wanted to do, and, back then, sports writers didn’t need degrees. Years later, William D. McCain, the college president, told Dad he couldn’t give him another raise unless he earned a degree. So, Dad got one. Still, he probably holds the record for this newest Hall of Fame. It took him 18 years to graduate.

My daddy, a most intelligent man, could have done most anything he chose. His oldest brother was the chairman of a college math department. Another older brother was a Georgia Tech-educated engineer. Two sisters were educators.

But Daddy loved sports and people. He found the perfect job for him, and he poured his heart and soul into it for more than 30 years.

He was good, really good, at it. He deserves this honor.

One more story, this one of more recent vintage. Dad was in I.C.U., after a bad stroke, and had been as close to death as you can get.

Bobby and I went in for one of the short visits. Dad asked if we had a paper. We did. Dad asked if we had worked The New York Times crossword. We hadn’t. “Well, read ’em out to me,” he said through tubes.

So we did. And he worked the puzzle without opening his eyes. Try it sometime. A nurse stopped what she was doing with all those machines, and just listened.

“What does he do?” she asked, obviously amazed.

“He’s just an old retired sports writer,” Bobby answered, most proudly.