Wee Willie ran straight into history

Posted on: October 18,2013

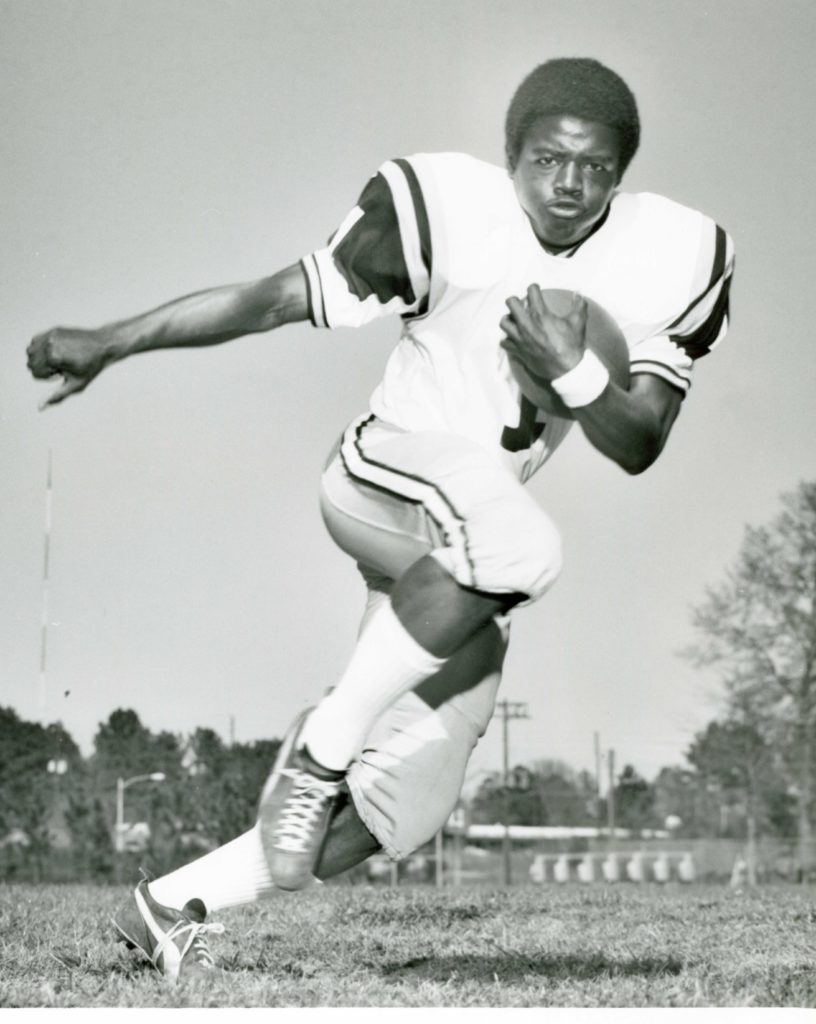

Willie Heidelburg, a football pioneer, died earlier this week at the age of 63. Services will be held Monday at 11 a.m. at Christ United Methodist where a huge sanctuary might possibly hold all those who will want to pay their respects to a kind, unassuming gentleman who played a huge role in Mississippi sports history, then became a beloved coach at Murrah and then Belhaven. What follows is the column I wrote on the 25th anniversary of the biggest

upset in Mississippi history, when Southern Miss stunned Ole Miss 30-14 in October, 1970.

upset in Mississippi history, when Southern Miss stunned Ole Miss 30-14 in October, 1970.Twenty-five years later, the memories remain vivid. When you’ve witnessed a miracle, you do not soon forget.

Memories…

Of Wee Willie Heidelburg, flitting like a water bug through much taller, heavier and so much whiter players.

Of Ray Guy’s punts, launched like missiles, high above even the press box at Hemingway Stadium.

Of Archie Manning, as gallant and amazing in defeat as ever in victory.

Of tired, sweaty Southern Mississippi players trying to carry their massive coach, P.W. “Bear”

Underwood, across the field to meet the legendary John Vaught. Of the players beginning to wobble, then dropping Underwood almost at Vaught’s feet.

Of Vaught, managing a smile and a quip. “Hell, Bear,” he drawled, “you couldn’t expect two miracles in one day.”

Of Underwood’s first remarks to stunned reporters, including yours truly: “This wasn’t an upset,” he boomed. “We took it to their butts and we whipped their butts.”

On that muggy day Oct. 17, 1970 Underwood’s USM team accomplished perhaps the greatest upset in Mississippi football history, if not college football history. Even today, a quarter century to the day later, the final score seems almost surreal: Southern Mississippi 30, Ole Miss 14. No, it couldn’t be.

But it was. It happened. It really did. And it really did change Mississippi football, forever.

Ole Miss was undefeated and ranked No. 4 in the nation. Manning, a senior, was considered the leading candidate for the Heisman Trophy. The Rebels were coming off victories over Alabama and Georgia. What’s more, they had swamped poor Southern 69-7 the season before. Southern had never beaten Ole Miss. Never.

Just the week before, Southern had been pummeled 41-14 by San Diego State. Earlier in the season, Auburn had dispatched Underwood’s team 33-14. Indeed, one week later, Mississippi State would drop a 51-15 bomb on Southern.

There was no betting line because Ole Miss was considered a prohibitive favorite. Will Grimsley, the venerable Associated Press scribe, picked Ole Miss to win the game 53-7. The Meridian Star daily newspaper went even further. The front page of the Oct. 17, 1970, Star sports section ran a photo of Manning pulling up his socks in the Ole Miss dressing room. The caption read: “Archie Manning . . . Is This One Worth Suiting Up For?”

The accompanying story began: “One of the greatest mismatches in the history of Mississippi collegiate football unfolds today when nationally ranked Ole Miss plays host to underdog rival Southern Mississippi on the Rebels new astroturf at Hemingway Stadium.

“Only a miracle could prevent Ole Miss from posting its fifth straight win of the year . . . two possibilities exist either the Rebels will try to pour it on or John Vaught will elect to take it easy on a seemingly outmanned USM unit.”

Southern fans were prepared for the worst. Take the case of a charter plane filled with supporters that flew from Hattiesburg to Oxford the day of the game. Approximately 60 boosters, including many USM employees and coaches’ wives, were on board. Most put up a dollar and wrote down a predicted final score. The one closest to the final score was to get the entire pot. Only one, then-USM sports information director Ace Cleveland, picked Southern to win.

A miracle?

Twenty-five years later, Underwood, who still lives in Hattiesburg, absorbs the question and pauses only briefly before answering, “All I can say is the best team on the field that day won the football game. We were the best team that day. We deserved to win and we won. I’ve heard it called the biggest upset in history and all that, but the best team that day won the football game.

“I know I said it wasn’t an upset, and, sure, it was. But what I meant that day is it wasn’t a fluke. I meant that we took the fight to them and we whipped them. That’s what we did.”

Underwood says he and his staff didn’t spend a lot of time that week trying to fire up the players. It simply wasn’t necessary. “The toughest thing for us was to keep them from getting too emotional too early,” Underwood remembers. “We didn’t want them to play the game on Wednesday or Thursday.

“All week long we talked about doing the little things right. We constantly drilled them on that that if they did the little things right, played sound fundamentally and didn’t make mistakes, that they would win the game. We didn’t talk about if we could win. We acted like we were going to win.”

Whether or not the Southern players really expected to win is debatable. Probably some did and some didn’t.

Rick Donegan, Southern’s tiny but strong-armed quarterback, had suffered three interceptions the year before in the 62-point loss to Ole Miss. Still, he remembers a confident Southern team that took the brand new artificial turf that day.

“We were not in awe of them,” says Donegan, who now lives just outside of Tupelo. “I’m not saying everyone thought we would win, but we all thought we had a shot.”

“I thought we could win,” says Heidelburg, who had transferred that summer from Pearl River Junior College and was Southern’s first black football player.

Other Southern players weren’t nearly so confident.

“We just wanted to be competitive with them,” says Craig Logan, then a USM cornerback, who lives in Oak Grove. “I don’t think many of us were really thinking win.”

Hugh Eggersman, the defensive end who became famous that day, certainly was not. “I considered it almost a given that they’d beat us,” Eggersman says. “My feeling was one of let’s keep it close, let’s don’t get embarrassed.”

No matter what they believed, they all performed magnificently. Donegan, all 160 pounds of him, completed 14 of 30 passes for 116 yards and also had a key 42-yard run. Logan, assigned to one-on-one coverage against the Rebels’ splendid receiver, Floyd Franks, intercepted two Manning passes. Eggersman claimed National Lineman of the Week honors with eight tackles, including one of Manning on fourth down at the goal line, and two sacks. And Heidelburg, who had said in the preseason that his goal was to score one touchdown against Ole Miss, scored two.

But for an upset of such magnitude, it took more than an inspired Southern team playing well. It also took an overconfident Ole Miss team playing far below par. Vaught had warned the Rebels all week against overconfidence. For one thing, Vaught knew the 1969 game had been an aberration. The Rebels had always won, but they had usually struggled against Southern until the 69-7 blowout.

“Southern is like anyone else,” Vaught warned. “They’re capable of beating you on a given day.”

Manning’s not sure that message ever sank in.

“I think it was purely a case of senior-itis,” Manning now says. “We had a bunch of seniors who had been around and probably thought we knew everything. We probably didn’t take it seriously enough. It was a perfect example of one team being really ready and the other team not being ready. It’s just proof that you can’t just roll your helmet out there. You gotta be ready, and we weren’t.”

Underwood, who had played down emotions during the week, became highly emotional just before the teams took the field. With the fervor of a Baptist preacher at a tent revival, Underwood challenged his players’ character. He held up the Meridian Star sports section, the one with the photo of Manning dressing, and boomed, “This is what people think of you! Go out and prove them wrong!”

The worst possible thing that could happen to Ole Miss happened on the Rebels’ first possession. Manning hit Franks, easy-as-you- please, with a 51-yard touchdown strike. Again, the memory is vivid: Manning launching the perfect spiral and Franks gathering it in without breaking stride right at the goal line.

“I can actually remember guys coming to the sideline saying, ‘Let’s get two or three more and then take it easy,'” Manning remembers.

For Ole Miss, nothing was easy after that. That was primarily because of Guy, whose rocket shots kept Ole Miss starting from deep in its own territory. Guy punted 10 times for a 49-yard average. He also kicked a 47-yard field goal just before half that gave Southern the lead for good, 17-14.

“Every time we got the ball we had 90 yards in front of us,” Manning says. “Ray was just amazing.”

Southern also had a 5-foot, 6-inch secret weapon named Heidelburg. Underwood had used

Wee Willie sparingly beforehand, mainly because he wanted to keep all of Heidelburg’s 143 pounds in one piece. For Ole Miss, USM offensive coordinator Dick Steinberg installed a new play. It was a wingback reverse with Heidelburg carrying the ball. Southern called it twice in the game. Wee Willie scored twice, both on 11-yard runs.

Long-time New Orleans Saints scout Hamp Cook, then USM’s offensive line coach, laughs when he remembers the play.

“The first time we ran it, it fooled them,” Cook says. “But the second time, they were all yelling, ‘Watch the reverse, watch the reverse!’ They knew it was coming, but they still couldn’t stop it. I couldn’t wait to get back home and see it on film and see what a great job my guys had done blocking.

“Hell,” Cook says, laughing harder, “we didn’t block anybody. Willie just dodged every one of them.”

Heidelburg was the quickest man on the field and the Ole Miss Astroturf made him just that much quicker. Heidelburg stuck out that day like a black dot on an ivory domino.

“To my knowledge, there was one other black person in the stadium that day, and I think he was the Ole Miss equipment manager,” says Heidelburg, a Murrah High assistant coach for 22 years.

Heidelburg’s first touchdown tied the score at 14. Then Guy’s kick gave USM the lead.

“When we were walking to the locker room, both teams went up the same walkway,” Eggersman says. “All their guys were shaking their heads, cussing and saying stuff like, ‘Can you believe this?'”

Heidelburg scored again on Southern’s first second-half possession and, suddenly, Ole Miss was in trouble. By then, even the doubting Southern players had grown confident.

“It was like we were in a zone,” Eggersman says. “You read and hear about golfers or tennis players getting in a zone. Well, we were a whole team in a zone. Everybody was playing over their heads. I mean, you had to see it. I was the tallest lineman we had and I was 6-foot with my hair pushed up. Our nose guard, Johnny Herron, was listed 5-9 but he was shorter than that. All their guys were 6-3 and 6-4. Heck, Archie was bigger than any of us.”

Yet, Southern seemed to grow as the game went on. Manning, who was slowed all day by a groin injury, took a brutal beating. “I’ve never been beat on so much,” he said at the time. “When those guys hit you, they hit you good.”

And yet when Vaught sent in Shug Chumbler, Manning’s backup, during the final seconds, Manning sent Chumbler back to the sidelines, as if to say, “Hell no, I’m not quitting.”

What must have seemed like an eternity to Manning and Ole Miss was over in a heartbeat for Southern players.

“Funny thing, I remember the first half better than the second,” Eggersman says. “The second half is like a blur. It went by so fast. It was like a dream really.”

Logan concurs. “It was like we were in a trance we were so focused,” he says. “I remember looking over and seeing all our fans coming down toward the field. They were jumping up and down screaming and celebrating. That’s when I looked at the scoreboard and saw there were only seconds remaining. I thought, ‘My God, we’ve won! We’ve really won!’

“In all my time in football, that was the one day when everybody on the team played as well as they could possibly play,” Logan says.

Manning completed 30 of 56 passes for 341 yards. The 56 passes are still an Ole Miss single-game record. He earned the everlasting respect of the Southern players who kept knocking him down and watching him get back up and fire another strike. “What a great player he was,” Logan says.

Indeed, Manning’s nobility in defeat made the victory all the more meaningful to Southern.

“To this day when you hear people talk about it, they talk about how we beat Archie and not just how we beat Ole Miss,” Hamp Cook says.

Upset or not, fluke or not, the game changed Mississippi football in many ways.

The then-No. 4 Rebels haven’t been ranked as high since. Vaught, who led Ole Miss to so many glorious victories in so many glorious seasons, suffered a heart attack two days later and retired from coaching following the 1970 season.

For Southern, it meant instant respectability for a school often referred to as Hardy Street High. No doubt, the victory over Ole Miss did more than anything else to help Southern’s drive to secure funds to more than double the seating at Faulkner Field for what is now M.M. Roberts Stadium. Southern would beat Ole Miss five more times before the series was discontinued in 1984.

Still, there can be no doubt that Heidelburg signaled the biggest change. Wee Willie, who carried the ball only three times that day, was the first black player to help one of the state’s predominantly white universities win a big football game. Of course, he was the first to ever have that opportunity.

Heidelburg and his teammates showed, quite dramatically, that whites and blacks could work together and play together and be better for it. He paved the way for the Reggie Colliers, the Sammy Winders, the Buford McGees and the Eric Mouldses who would come later.

Ole Miss signed Ben Williams, its first black player, the next year. Now, Ole Miss, State and USM teams are all about half black, half white.

In retrospect, Heidelburg says he never thought about being a pioneer. “I just wanted an education and I wanted to run the football, and Southern gave me a chance for both,” he says.

And 25 years ago, Willie Heidelburg ran that football right into the end zone and straight into history.

•••

To support your Mississippi Sports Hall of Fame and Museum, click here.